Anorexia Nervosa: Its History, Psychology, and Biology (1960) by Dr. Eugene L. Bliss

By Kalea Spurlock

Anorexia Nervosa: Its History, Psychology, and Biology (1960) by Dr. Eugene L. Bliss is one of the earliest books written about anorexia nervosa. Though the disorder has been studied for hundreds of years, with the first possible written case dating from 1542, this was one of the first collections published.

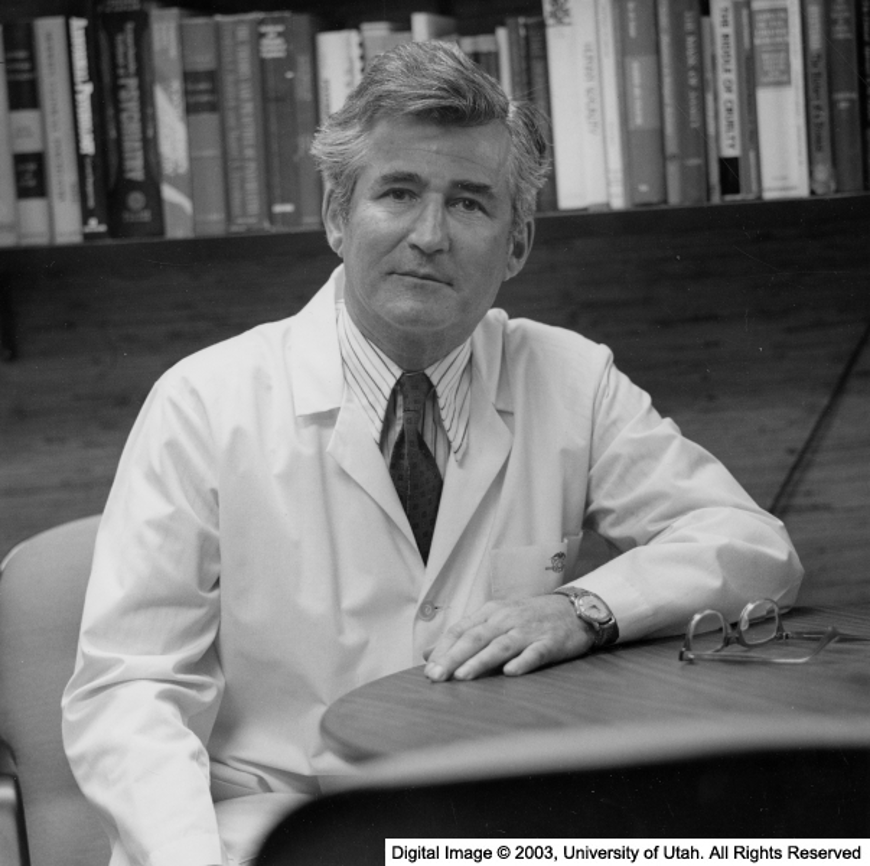

Bliss specialized in psychiatry, and after he graduated from the New York Medical College, he trained at the Menninger Institute. After serving in the European Theatre during WW2, he joined the faculty at the University of Utah, College of Medicine, in the Department of Psychiatry, where he eventually became chairman (1970-1979) [1, 2].

The beginning of the book brings up the history of extreme fasting. Fasting to this extent isn’t found in ancient cultures as much as it is in modern primitive ones. Fasting was used in part of the mourning process or as societal initiation, like a rite of passage. There is also the use of fasting as an ascetic practice, which helps separate the “evil body and the pure soul” [3]. Fasting occurred in most religions, and the use of more extreme fasting was common in the early days of Christianity. However, over time the practice of extreme fasting lost its religious associations.

In the early 1870s, Charles Leseque first described anorexia nervosa by the name “l’anorexie hysterique,” which in the early 20th century was renamed anorexia nervosa. Bliss recounted this information and more when talking about the history of the disorder, giving the reader and intended audience background on the importance of the topic and the general development of the disorder.

Bliss also questioned the contemporary diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa. For a long time, a patient had to be severely underweight, along with several other criteria, in order to be diagnosed with anorexia. However, during his case studies, he observed several patients who were not at a dangerous weight, nor did they have dangerously low vitals; but they had lost significant amounts of weight and showed many of the other signs, such as a fear of weight gain, or a form of repulsion toward food. Bliss references several other studies and papers about patients that suffered from more extreme cases of anorexia nervosa, including ones where the patient lost an incredibly large amount of weight, and ones where the patient’s weight at the beginning of treatment was extremely low.

Patients featured in Bliss’s case studies reported various reasons for avoiding food such as a fear of gaining weight, or the idea that food symbolizes babies and other body parts. Along with several observations of treatments that Bliss used in his own practice, and those reported by other doctors, he argued that the proper course of treatment for anorexia nervosa is a case-by-case decision.

One very important observation Bliss made was that contemporary beauty standards were a significant reason for the development of anorexia nervosa. The beauty standards that we should be looking at would be those of the 1950s since this is when Bliss was working on the study. The fear of gaining weight is one of the most common reasons for developing an eating disorder, but it can be combined with other causes as well.

An analysis of the beauty standards from the 1950s all the way to today makes it clear where this fear can stem from. The ideal body shape and size around 1960 was small and borderline emaciated. There was a significant pressure on women to conform to the socially accepted beauty standards. This can cause a significant number of psychological issues within women. To many of the patients, being thin meant that they were attractive and seemed ideal in a way. Several patients had also been obese as either children or teenagers, and had been outcast by their peers because of their weight. So, to them, being overweight meant that they were ugly and didn’t deserve to be happy [4].

Whatever reason a person might have for developing anorexia nervosa or other eating disorders, these conditions can become the sole focus of their life. Bliss recounts one patient that he treated and her thoughts about how food represented other things in her life, such as a baby, affection, and parts of the reproductive system, and whenever she ate, she could only think of those associations [5].

There were treatments that worked for some patients that did not work for others. For some, forced feeding and hospitalization worked, for others returning home was more effective. For some patients, talk therapy worked and they were able to go into remission, but for others, more extreme treatments, like surgeries, worked. This can also be looked at the other way around, as some patients reacted badly toward surgeries and talk therapy. Every case of anorexia nervosa is unique and must be treated as such. One thing that we can observe from reading this book is that there is still a significant amount more to learn.

(This post was written for the course HIST H364/H546 The History of Medicine and Public Health. Instructor: Elizabeth Nelson, School of Liberal Arts, Indiana University, Indianapolis).

References:

[1] “Bliss, Eugene L., M.D.,” History of the Health Sciences, Spencer S. Eccles Health Sciences Library, University of Utah, 2003, https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6t75spr.

[2] “Eugene Bliss Obituary, 1918 – 2018,” The Salt Lake Tribune, May 13, 2018. https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/saltlaketribune/name/eugene-bliss-obituary?id=1655730.

[3] Eugene L. Bliss and C.H. Hardin Branch. Anorexia Nervosa: Its History, Psychology, and Biology. New York, New York: Hoeber, 1960.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.